The link between regional economic growth and health equity

Written by: Sarah Dew - 8th November 2023

There is a live and active conversation happening in UK politics about the role of regions, places and devolution in tackling regional economic inequality. In this blog, Sarah Dew, Programme Director of the South Yorkshire Innovation Hub, sets out some reflections on this policy debate, and what we can learn from it for developing a regional infrastructure for health and care delivery.

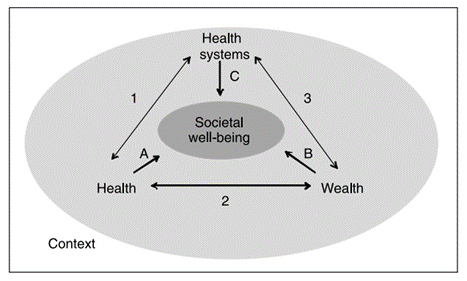

That health and wealth are intricately linked is well proven. This is true at an individual level, and at a societal level. The Health Foundation found that ‘31% of people on the lowest incomes report ‘less than good’ health. In the middle (the fifth income decile) this figure is 22% and for people on the highest incomes the figure is 12%’ (2019/20 data). At a societal level, health helps create wealth through improving wellbeing and increasing economic participation, and wealth helps create health through improving health systems and the health of individuals. The European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies set this out helpfully in the conceptual framework below, where health, wealth and health systems have interlocking roles in shaping societal well-being.

Given this important relationship between health and wealth, I’ve been following the Harvard Kennedy School’s research series into regional economic inequality in the UK with great interest. They are exploring why the UK’s poor performance against a variety of measures of regional inequality has seen it labelled as ‘the most unequal large industrial country’ – and what the relationship is with the way in which we have approached regional economic policy and our heavily centralised approach to governing.

Their first paper looked at the defining features of this regional inequality problem. Their most recent paper brings together an impressive 90+ on the record interviews with political and civil service leaders over the last 45 years to identify the main lessons for policy makers today looking to address this regional inequality problem.

As someone living and working in health and care and in one of the ‘underperforming non-London cities’ as described in these papers, I have a deep personal and professional commitment to addressing the increasing disparities in health and the underlying economic inequalities. I found these interviews to be enlightening and thought provoking.

The analysis focuses on the implications for the relationship between local, mayoral/ regional and national governing infrastructure – but there are parallel lessons for health systems, which are going through their own transition to place based governing structures in the form of Integrated Care Partnerships and Integrated Care Boards to drive improvements in health and reduce health inequalities.

In this blog, I’ve captured some of my key reflections from reading Dan Turner, Nyasha Weinberg, Esme Elsden and Ed Balls’ paper that synthesises these 90+ interviews on the insights we can apply to developing effective regional health leadership.

The importance of vision, purpose and aligned incentives

One of the leaders that Turner et al interview in their research is Howard Bernstein, who says that “place leadership” must precede “place planning”. He continues by explaining that “a good planning system is no replacement for a clear, integrated vision for a place that can sustain and coordinate investments over a long period of time” and powerful leadership to steward and promote that vision.

This is a useful reminder for any significant transformation agenda. In South Yorkshire, the benefits of Mayor Oliver Coppard chairing the Integrated Care Partnership is evident. He champions the Partnership’s vision that everyone in our diverse communities lives a happy, healthier life for longer and can galvanise partners beyond the health and care sector around this shared vision. As the regional infrastructure of our health system develops, this local vision, which is grounded in an understanding of our region’s challenges, will be a north star.

Regional places also need the autonomy to translate this place leadership meaningfully into their own measures for success. Gordon Brown is quoted in the paper with the view that “once you set up targets and make that your defining criterion for success, inevitably it will push you towards a greater degree of centralisation […] that was the reason why everything went through the centre.” As the role and function of Integrated Care Boards develop, this is a useful lesson for national leaders that genuine place leadership can only grow when there is meaningful ownership of measuring success at the place level against outcomes set by that place.

Health is a regeneration tool and should be recognised and deliberately planned as such

Transport infrastructure between regions is a hot topic for how we can reduce regional economic inequalities, and has been particularly so in recent months. The interviewees in the study recognise however that “increasing funding and prioritisation of public health and early years support” may be an incredibly effective, and under recognised, regeneration tool.

Kitty Ussher, formerly a Special Adviser at the Department for Trade and Industry and Treasury Minister, is quoted as saying that the regional policy failure on economic growth should be considered much more broadly than transport, and that “affordable childcare and the ability to be able to commute to where the jobs are, to get part-time promotion” are powerful levers for change – and interestingly argues that the lack of focus on this area may be linked to the limited diversity of those in leadership roles shaping economic policy.

The fourth core purpose of Integrated Care Systems is to ‘help the NHS support broader social and economic development’, and it is exciting to see the new focus that the South Yorkshire Integrated Care Partnership infrastructure is providing to draw the links between local authority, mayoral combined authority and health and care bodies to consider health and care (not just the NHS) as a tool for economic growth (which, in turn, if driven inclusively can help improve health inequalities).

Research and innovation, and the universities that help initiate much of this activity are engines for growth

Sir Tony Blair says in his interview “We didn’t really, until the end, start to understand the absolutely crucial relationship that was starting to develop between universities and economic development, which I think today is absolutely central.” Universities are powerhouses of research and innovation, and the spill over benefits of this activity for economic growth are, as Blair says, only beginning to be fully recognised.

In South Yorkshire, we have an impressive set of research and innovation strengths in health and wellbeing in our two universities. We are building ever closer working relationships to think about how this expertise can both help us to directly improve the care that is provided across our four places, but also how we can recognise these assets as key engines for our regional economic growth and take more coordinated action to use health innovation and research as the fuel for growing prosperity in the region.

Be mindful of unintended consequences

The transition to Integrated Care Systems in health and mayoral leadership in political governance is driven by a growing recognition that place-based leadership can more effectively address local issues due to its proximity to on-the-ground challenges and the mechanisms for delivery, which are challenging in a heavily centralised system.

However, Joe Irvin (Special Adviser to John Prescott) said that “it’s not a given that devolution is a good thing, and we have to think about it… one person’s devolution can also be another person’s postcode lottery.” This is a useful reminder of two things: firstly, that we shouldn’t be ideological about what we think is the ‘right’ way to develop and deliver policy – we must be led by evidence on the ground. Secondly, that when it comes to how we oversee the delivery of health and care services at a regional level, we need to focus on quality and equity, and prove the thesis that leadership closer to communities and to delivery can improve outcomes through more tailored and responsive service provision. These are easy things to say and hard things to do, and a laser focus on reducing health inequalities and increasing health equity is a key leadership role for Integrated Care Boards and Integrated Care Partnerships going forward.

In the paper the authors say that it was challenging to summarise around a half million words’ worth of conversation into one paper – and so too it was difficult to pick out just a few key takeaways from their paper for this blog! There is further work to come from this group, and I look forward to continuing to follow that with interest – as well as to progress the work the Innovation Hub is taking forward in partnership with colleagues across South Yorkshire to recognise and promote the role of health research and innovation to address inequalities in the region.

In this complex space, there are no obvious answers, so I would love to hear the views and reflections of others.